Who was Kaspar Hauser, named “the Child of Europe”, really? A question the people of Nuremberg and beyond have been asking for almost 200 years.

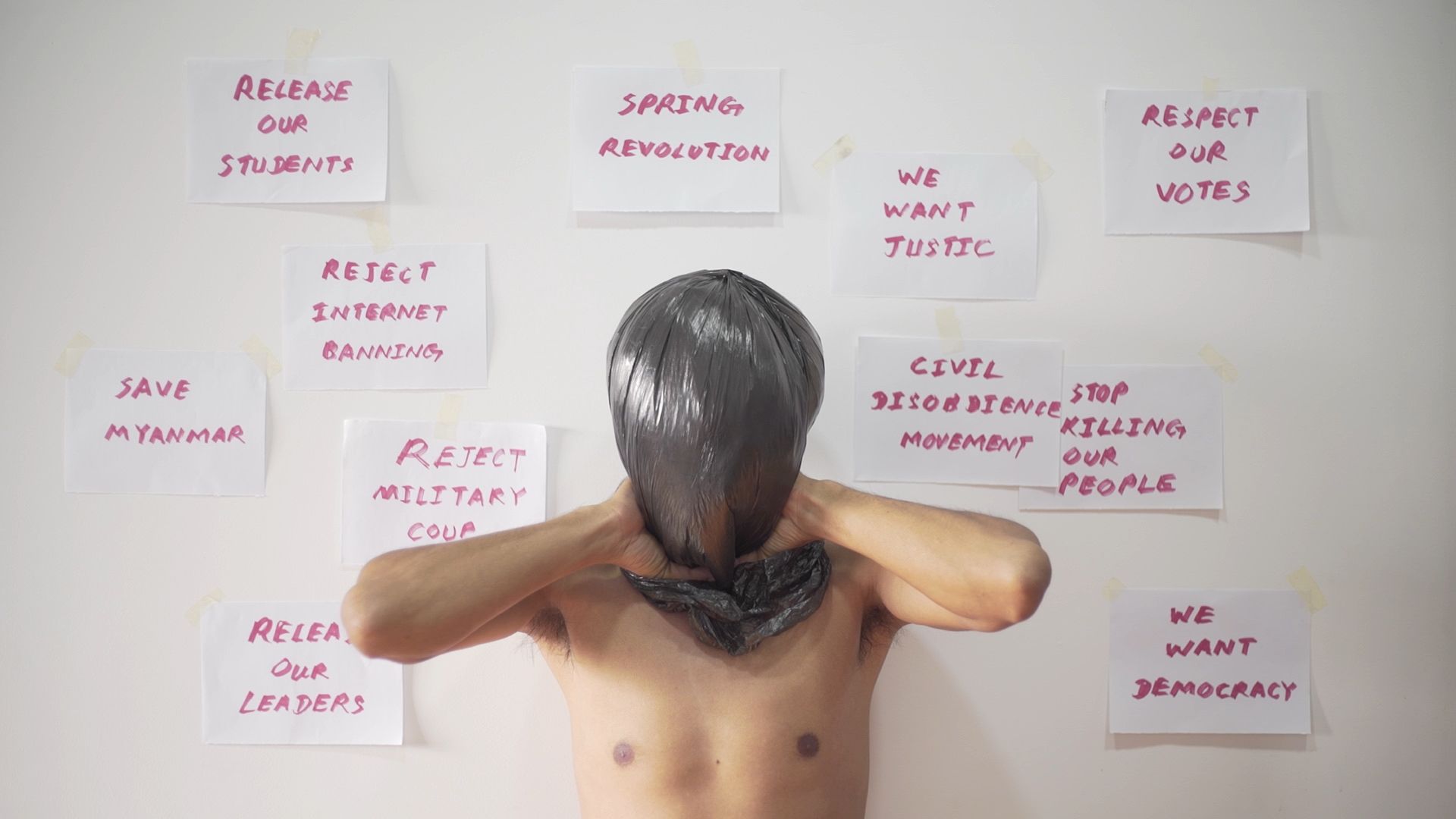

At the corner of Unschlittplatz in Nürnberg, a plate mounted on house number 8 reminds us of an event which has become famous far beyond the city walls. In the afternoon of the 26th of May, 1828, a boy about 16 years old suddenly appeared there. He could hardly speak, write, or even walk properly. It is claimed he had been locked alone in a dark cellar since an early age and fed on only bread and water, hence his apparent lack of all basic skills, social competence, and education.

The only understandable sentence, which he repeated time and again, was: “I want to be a rider like my father”. A police officer gave him a quill pen and ink with which the boy arduously wrote his name “Kaspar Hauser”. After all attempts to question him failed, he was locked up in the “Luginsland” tower. The event became a sensation not only in the town but throughout the whole region, and large crowds gathered at the castle to see him. A Nuremberg teacher called Daumer took the boy into his house where Kaspar was happy and made astonishing progress. An Englishman, Lord Stanhope spent large sums of money trying to establish Hauser’s origin and eventually took legal custody of him.

A year later in 1829, Hauser was attacked in the house where he was living and wounded badly. Following this first attempt on his life, Lord Stanhope moved him to Ansbach, about 50 miles to the south of Nuremberg. Here he lived in the house of the district judge, Anselm von Feuerbach. Hauser became a court clerk and seemed to find his place in society. The curiosity about his person began to abate, when suddenly in 1833 he was again viciously attacked, this time with fatal consequences. Only five-and-a-half years after his dramatic appearance, an unknown assassin lured Kaspar Hauser into the court gardens and assaulted him with a knife. Three days later Kaspar died of his injuries. Soon rumours began to spread that he was really a prince from the House of Baden. Others said he was a charlatan who was only seeking attention. The many rumours and conspiracy theories about his origin and mysterious death have kept the story alive. In 1996, “Der Spiegel” initiated a gene analysis of blood from Kaspar’s clothing which seemed to show he was not the Prince some had suggested. But in 2002, further analysis of his hair showed the blood was not Kaspar’s and that, although unlikely, he was possibly the son of the Duke and Duchess of Baden, and heir to the house of Baden. The House of Baden forbids any medical examination of the remains of Stéphanie de Beauharnais (Grand Duchess of Baden 1811 – 1818) or of her son who died as a child.

A very detailed and elaborate account of the enigma entitled “Kaspar Hauser, the Child of Europe – A synopsis” by Eckart Böhmer and translated into English by Helen Lubin is online and available here.

In Georg Trakl’s poem, “Kaspar Hauser Song” from 1913, Hauser is represented as lost, living in a strange world and lacking a sense of origin, home or attachment.