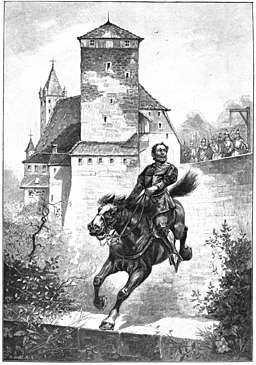

Well, this highwayman was certainly no dandy, but then he was from 14th century Franconia.

The districts around Nuremberg were once the dominion of a legendary highwayman known as Eppelein von Gailingen. Sentenced for his villainous deeds to execution by hanging at Nuremberg Castle, he won fame for his legendary escape. It is said that before his hanging he expressed a last wish which was to ride his trusty horse once more. All the gateways being heavily guarded, his wish was granted and he mounted his horse one more time, riding slowly to and fro across the courtyard. Suddenly, with a spur to the horse, he rode with lightning speed towards the fortification wall and he and his horse jumped over. The horse’s hind hoof catching the wall gave one last thrust of power supposedly carrying both rider and horse across the dry moat to land safely on the far side.

Today you can see the imprint of a horse’s hoof on the stone parapet at Nuremberg castle. If you look closely you can find not just one but several imprints in the shape of a horse’s hoof in the parapet stones! Looking across the wide and deep fortifications today, it might seem a rather improbable story. Still, it should be considered that in Eppelein’s’ day, when this extraordinary event is said to have taken place, the castle fortifications were not yet enlarged and improved. Others say the ground below was swampy and provided a soft landing.

Nuremberg Castle Hoofprint – Alice

After his escape, Eppelein came upon a farmer on his way to watch the execution. Not realising who he had before him the farmer asked Eppelein if the execution had already taken place to which Eppelien replied, “The Nuremberger aren’t hanging nobody, they’d have to have him first!” Over the centuries and to this day the people of Nuremberg are still mocked for this mishap with the line: “Die Nürnberger hängen keinen—sie hätten ihn denn zuvor!”

We can only guess how much of this story is true, but Eppelien did exist and robbed trading caravans during the 1360s. By all accounts, he was quite a wild character, witty yet reckless, a womaniser but also somewhat brutal. He could easily persuade those around him to partake in his audacious exploits. In the 19th century, Eppelein’s story was romanticised and celebrated as a Franconian Robin Hood character. Stories of his intrepid feats abound, although there is little historical evidence that he acted with altruistic intentions.

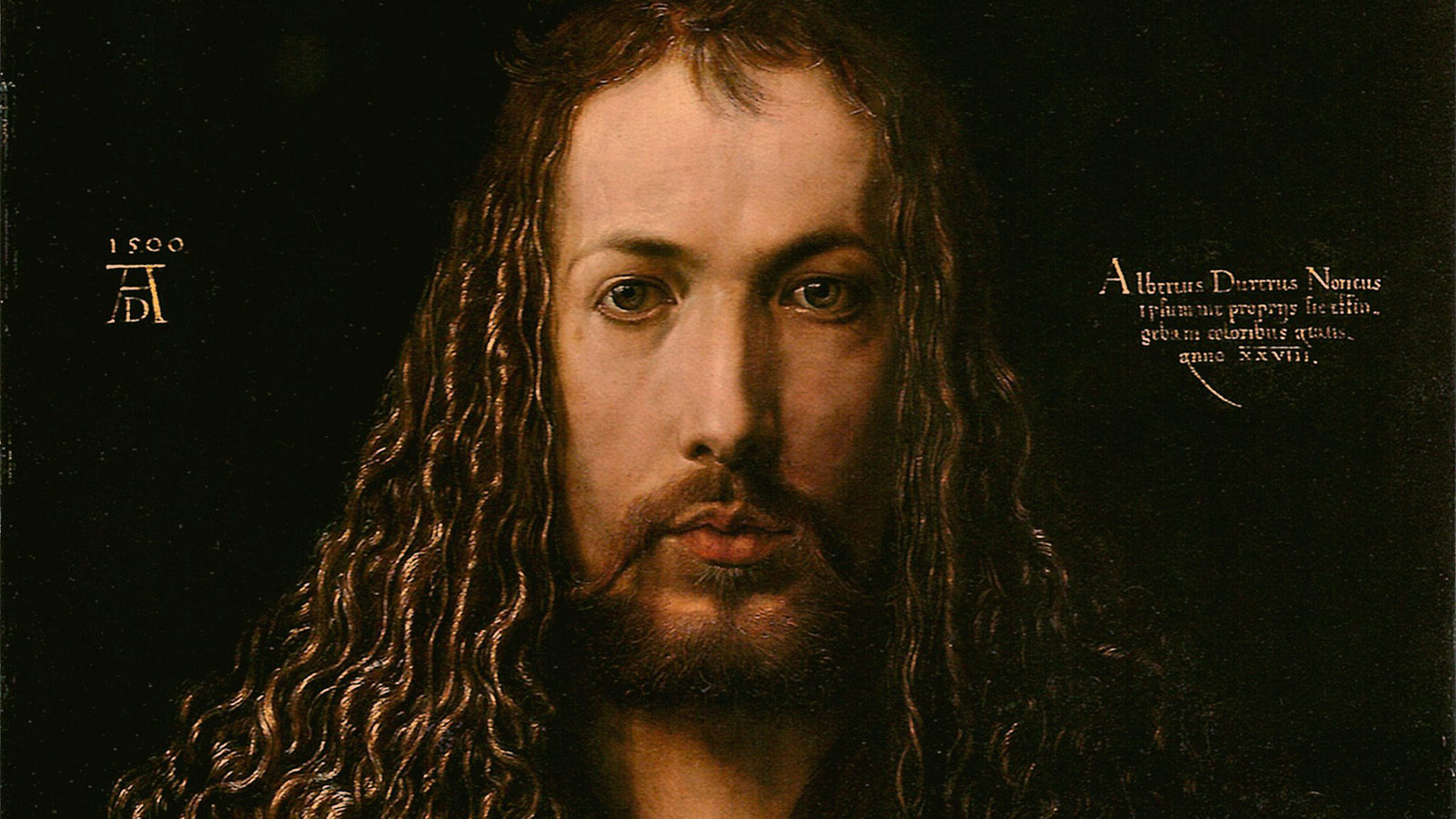

Born near Windsheim into the House of Geyling around 1320, he was given the name Apollonius. He is also referred to as Eppelein von Gailingen, Eckelein Geyling, Ekkelin Gayling and Eckelein Gailing. In 1330 his father, Konrad der Schwarze, acquired a castle at Wald (today it lies west of the Altmühlsee).

Eppelein married Elizabeth von Wildenstein with whom he had three sons and five daughters. Their home, supposedly in Franconian Switzerland at Castle Dramaus near Draynmeusel (today Trainmeusel) is said to have overlooked the Wiesent Valley near Muggendorf. In fact, a castle stable at Trainmeusel was first mentioned in documents around 1420 and the existence of Castle Dramaus is much disputed.

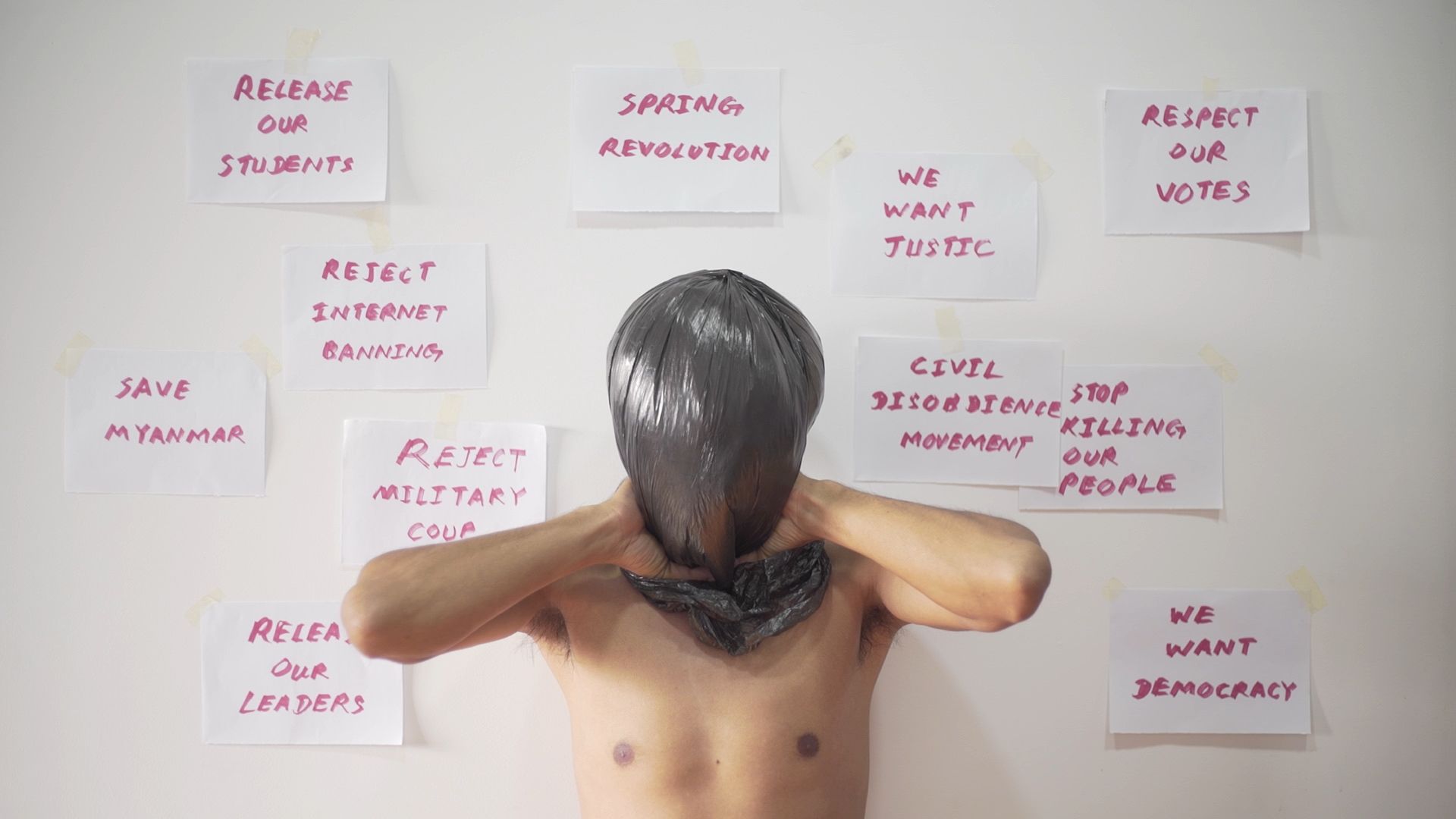

In the feudal system which existed in medieval society, Lords were granted land by the King and so became a vassal to the King. In turn, the Lords created their own vassals by granting Knights use of part of these lands as fiefdoms in return for military service. It was under this system that the knightly dynasty of the Geylings received smaller fiefdoms from the Counts of Hohenlohe.

This was also a time of change, the crusades had ended and the power of the Emperor was waning. The old order of knights in shining armour ruling from a castle over the serfdom of peasant farmers was coming to an end. Trade between cities was now flourishing and knights had, to some extent, outlived their purpose. Merchants, based in the growing cities were becoming the new powerbrokers in the land.

The expensive lifestyle of a knight, a professional warrior, including servants and weaponry could not be met by the meagre levees exacted from farmers cultivating a parched land. And so it was for our not-so-noble knight Eppelein from Gailingen. Having fallen upon hard times, he became jealous of the wealth and power the rich patricians in the city of Nuremberg were accumulating. In the 1360s, to supplement his income and support his accustomed lifestyle, he took to the highways, robbing merchants and their wagons as they passed to and fro from the great Imperial City of Nuremberg. Such knights were known as Raubritter (robber barons) and were not uncommon in the late middle ages.

In 1369, the Nuremberg court imposed the imperial ban on Eppelein, in effect declaring him legally dead and removing all his rights and possessions including his part of the Castle at Wald.

In a feud between the Count of Hohenlohe and Frederick V, Burgrave of Nuremberg in the 1370s, Eppelein fought on the side of his feudal lord but finally became a pawn in the game of the more powerful. An arrangement between the houses of Hohenlohe and Hohenzollern settled the dispute, but Eppelein was left penniless.

On 28th August 1375, Emperor Charles IV awarded Eppelein’s part of the castle at Wald to Frederick V, Burgrave of Nuremberg. Shortly afterwards Eppelein was betrayed and caught, he was imprisoned in Forchheim and sentenced to death by gallows in Nuremberg. As described earlier, however, he managed to escape by jumping his horse across the castle fortifications.

There was nothing left for Eppelein but to continue his plundering and there followed six years of success during which time he built a devoted following with up to 17 other knights and their servants. Alas, in 1381 he was eventually caught whilst binge drinking with friends in a public house called “Zum Schwarzes Kreuz” in PostBauer-Heng. (The public house “Zum Schwarzes Kreuz” still existed until quite recently. Today we believe it houses a Chinese restaurant, now what would Eppelein say to that?)

In Neumarkt, a town about 30 miles southeast of Nuremberg, he was hung, drawn, and quartered along with his two nephews Hermann und Dietrich Bernheimer. Four servants who had accompanied him on raids also lost their heads. Today there is a memorial in Neumarkt at the place where the executions took place. The costs for the capture and execution of the highwayman amounted to almost 1000 guilders, which remained unpaid by the City of Nuremberg until only recently. In 1998, at the State Garden Show in Neumarkt, the debt was finally paid to Neumarkt, if only symbolically, with chocolate coins!